Our next stop after Macedonia along the Balkan Peninsula was Bosnia and Herzegovina. Although it is one country, the terms “Bosnia” and “Herzegovina” refer to geographic regions of the country. The borders between the two regions are vague, but Bosnia makes up the bulk of the geography in the north and Herzegovina a small section in the south. Informally, and for the sake of my word count in this article, the country is often called just Bosnia (or BiH for short).

Our next stop after Macedonia along the Balkan Peninsula was Bosnia and Herzegovina. Although it is one country, the terms “Bosnia” and “Herzegovina” refer to geographic regions of the country. The borders between the two regions are vague, but Bosnia makes up the bulk of the geography in the north and Herzegovina a small section in the south. Informally, and for the sake of my word count in this article, the country is often called just Bosnia (or BiH for short).

Bosnia’s rich history is apparent just by strolling the streets of its capital city Sarajevo today. From the mid-15th to the late 19th centuries, the Kingdom of Bosnia was annexed by the Ottoman Empire. Today, we see the evidence of the Ottomans in the old bazaar area, called Baščaršija, and the presence of so many minarets that dot the skyline. For the forty years leading up to the end of World War I, the region was brought under the umbrella of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy. The main pedestrian street is divided into Ottoman (where it is referred to as Saraci Street) and Austro-Hungarian (where it is called Ferhadija Street) ends, and there is a sudden and obvious break between the two; the low red-tile roofs and narrow cobblestone streets of the bazaar give way to tall, grand facades.

Speaking of the First World War, remember how it started? On June 28, 1914, a Bosnian Serb and Yugoslav nationalist named Gavrilo Princip and his conspirators assassinated the heir to Austria-Hungary, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, and his wife, Sophie, Duchess of Hohenberg, in Sarajevo. Austria-Hungary then issued an ultimatum to the Kingdom of Serbia. Serbia looked to its allies (the U.K., France, and the Russian Empire, and then later Italy, Japan, and the U.S.) for help, and Austria-Hungary called on Germany (and then later the Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria), and this complicated web of alliances ended up resulting in one of the deadliest wars in the history of humanity. We saw the cemetery where Princip is buried in Sarajevo, and this very bridge is where the assassination occurred.

After the end of WWI, Bosnia was part of Yugoslavia until its declaration of independence in 1992, which resulted in the devastating Bosnian War. Bosnia is home to three main ethnic groups: Bosniaks (Muslim and about half the population), Serbs (Orthodox and about one-third of the population), and Croats (Roman Catholic and about 15% of the population). Because of its diversity, Sarajevo is often referred to as a “mini-Jerusalem,” and a walk along the main street will take you past mosques, Orthodox and Catholic churches, and synagogues. Nowadays, this diversity is a delight, and visitors can enjoy a range of cultures and cuisines in one location. But, only 20 years ago, these ethnic differences resulted in a tragic outcome.

To set the stage a little bit, and also since these events will be relevant during the next Montenegro and Croatia legs of our trip as well, let’s talk about Bosnia during most of the 20th century. At the end of WWII, the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia was formed from the union of six constituent republics (Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia, and Slovenia, plus the two autonomous provinces of Kosovo and Vojvodina), and President (for Life) Josip Broz Tito succeeded in keeping nationalist tendencies of these republics largely at bay until his death in 1980. Although he was a dictator, Tito is still very popular among the people of this region, and many streets and squares are named for him. Times under Tito were regarded as prosperous and peaceful, and Sarajevo’s international status was reinforced in 1984 when it hosted the Olympic Winter Games.

In the decade following Tito’s death, nationalist tendencies reemerged and caused tensions among the ethnic populations. On one side, republics like Croatia and Slovenia were eager to break off, and both declared independence in 1990. On the other side, Serbia was intent on preserving the union in Yugoslavia and keeping all the ethnic Serbs living in the different republics under the same governing umbrella. This was epitomized by Slobodan Milošević and his plan for a “Great Serbia.”

In Bosnia, this meant that the Bosniaks and Croats were in favor of independence, while the Serbs wished to remain in the Yugoslav federation. Bosnia declared independence in October 1991 and held a referendum on February 29 and March 1, 1992 to reinforce the government’s decision. A majority of Serbs boycotted the vote, and the remaining 63% that turned out voted overwhelmingly for independence (which was subsequently recognized by the international community). In the month following the vote, episodes of conflict broke out throughout Bosnia between the Serbs and either the Bosniaks or the Croats.

A peace rally was held in Sarajevo on April 5, 1992, and Serb forces opened fire on the crowd. The next day, the Serbian forces besieged the city of Sarajevo in what would become the longest siege of a capital city in the history of modern warfare (1,425 days… that’s one year longer than the Siege of Leningrad during WWII). Although in the minority, Serb forces in Bosnia were superiorly armed and supplied by the Yugoslav army and quickly gained significant control of the country. In Sarajevo, the Bosniaks and Croats were allied against the Serb insurgents. Elsewhere, like in our next destination of Mostar, Croats fought Bosniaks.

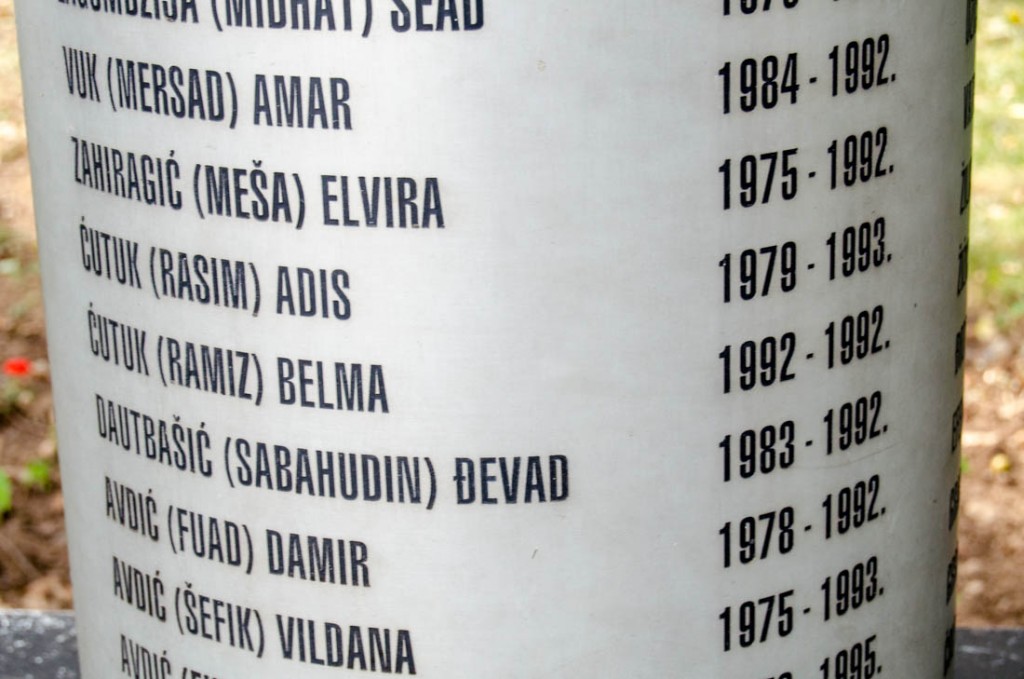

We saw the remaining physical evidence of the siege during a “Times of Misfortune Tour” we took while in Sarajevo. For nearly four years, the city of Sarajevo was cut off from the outside world and constantly bombarded with heavy artillery from the surrounding hills. The citizens were left without food, water, medicine, and had no electricity or heating. Snipers took up position in high rises and key streets became known as “snipers alleys.” Two of the snipers’ victims were Admira Ismić (a Bosniak) and Boško Brkić (a Bosnian Serb), high school sweethearts who were gunned down together on a bridge in Snipers Alley as they tried to escape the city; they were found dead holding hands. PBS turned their story the documentary Romeo and Juliet in Sarajevo.

An average of 329 shell attacks per day hit the city of Sarajevo, reducing much of the city to ruins. Hospitals, funerals, sports matches, and even maternity wards were common targets. Eventually, the city’s defenders would resort to digging a tunnel under the U.N.-controlled airport into Bosnian-controlled territory outside the city to bring in supplies and weapons.

War crimes, including group executions, imprisonment and mistreatment of women and children, and even torture and rape camps, were committed by both sides during this time, though Serbian forces were accused of them on a much larger scale than the other contingents. In the bloodiest of incidents by the Serbs, the Srebrenica massacre of over 8,000 Bosnian Muslims was ruled as genocide by the International Criminal Tribunal. The two massacres of civilians at the Markale marketplace in Sarajevo and the Srebrenica genocide finally prompted a NATO intervention. In December 1995, the three sides, under heavy pressure from Europe and the U.S., signed the Dayton Peace Agreement to halt fighting. The Siege of Sarajevo was finally lifted in 1996.

Bosnia has remained shockingly peaceful in the twenty years since the end of the war, but its impact is still being felt today. The terms of the Dayton Agreement, which was meant to be a temporary solution, still largely govern Bosnia. The country was divided into two entities—the Republika Srpska and the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina—but power was significantly decentralized. There are three Presidents and an incredibly complex government structure that makes it nearly impossible to get anything done. Bureaucracy eats up a huge portion of spending, and unemployment remains high for the rest of the people. Yet in the face of all these challenges and without any meaningful government assistance, Bosnia is seeing one of the highest growth rates for tourism in Europe. After visiting Sarajevo, we can say that this surge is for a reason. Sarajevo’s picturesque mountains make for gorgeous views in the summer and great opportunities for snow sports in the winter. Its rich cultural heritage results in a diverse and friendly population and amazing local eats. Chris and I had a great time sampling some of the local fare during our time in Sarajevo.

Despite the tensions that linger, one thing that is undisputed is Sarajevo’s jaw-droppingly gorgeous sunsets. Pick any of the surrounding hills to climb up around 7pm, and you’ll be treated to spectacular views. The sky casts a pink glow, turning all the houses the same warm, rosy color that almost, just almost, obscures the lingering damage to the city below.

Somber Sunsets indeed. Lauren, thanks for sharing a lot of the Sarajevos history and the context of the Bosnian war of the 1990s – I learned alot just by reading your post! Miss you! Love to Chris!

Thanks, Mary 🙂 Love you as well!