We planned to spend the bulk of our week in Poland in Krakow, the cultural capital of the country. Krakow was also the governmental capital of Poland throughout much of the land’s history and is still bitter about King Sigismund III moving the official center to Warsaw in 1596. [Funny bit of folklore about that, by the way. According to both our tour guides in Warsaw and Krakow, Sigismund III was an amateur alchemist in pursuit of synthesizing gold and accidentally burned down part of the Royal Palace on Wawel Hill. He decided it was easier to move the capital to Warsaw than rebuild!] Conversely, Varsovians are proud of their capital-city status and honor the guy with a column in the center of Castle Square.

How Krakow’s Old Town Survived the War

Because of its centuries as an imperial center, Krakow is decorated with castles, squares, fortresses, and cathedrals. During its golden age in the 15th and 16th century, Krakow blossomed economically, drawing people from all over Europe, and experienced its own Renaissance in art and architecture. Unlike Warsaw, Krakow survived the tumultuous 20th century largely intact (we had a chance to view many of these hundreds-year-old works like Altarpiece of Veit Stoss in St. Mary’s Basilica and the courtyard of Wawel Castle ourselves during our stay here).

Speaking of the Wawel Castle (and totally unrelated to anything else I’m going to talk about during this post), a small but distinct set of visitors come to Wawel Hill for a totally different reason than to view the Renaissance courtyard or visit the tombs of Polish kings. According to a number of different beliefs (which you can read about here on Wikipedia if you care to learn more), Wawel Hill—specifically the northwest corner of the courtyard—is thought to be the location of one of the seven chakras of the Earth, meaning one of the world’s strongest sites of spiritual energy. I only learned about this from our tour, as authorities discourage these theories and the related new-age tourism they bring. You can see the wall behind (which they try to hide with signage) is dark from finger marks of people trying to charge their chakras.

Anyways, back on topic: Why did Krakow’s cityscape survive relatively unscathed while Warsaw was almost completely razed? Well the Nazis were intent on preserving the city, which they viewed as a “pre-German” place (Krakow was annexed for a time by Austria in the 19th century). Hans Frank, Hitler’s lawyer and the Governor-General of occupied Poland, set up Nazi party offices in Wawel Castle. The Nazis envisioned turning Krakow into a completely German city (after removing all the Poles and Jews) and sponsored propaganda to portray Krakow as historically German. The German spelling “Cracow” is still widely used today (though Poles actually use the Kraków spelling and pronounce it like “Krak-uf”).

The Tragedy of the Jewish Quarter

After the invasion of Poland at the start of World War II, Krakow became a key command center for the Nazi government. Suspicious and hateful of the large population just south of the city center, the Nazis would eventually move the entire Jewish population of Krakow either out of the city or into a walled zone that would come to be known as the Krakow Ghetto, before eventually moving them to concentration camps. The Nazis forcibly relocated Krakow’s remaining Jewish population from the historic Jewish Quarter, called Kazimierz, into the ghetto. To give you a sense of what life was like in the ghetto, 15,000 Jews were crammed into an area previously inhabited by 3,000. It was roughly one apartment for four families. The ghetto was liquidated by March 1943, and most of its inhabitants were sent to their deaths at nearby concentration or extermination camps. Before the German invasion of Poland, 70,000 Jews lived in Krakow. Today, there are only 100 registered members of the Jewish community.

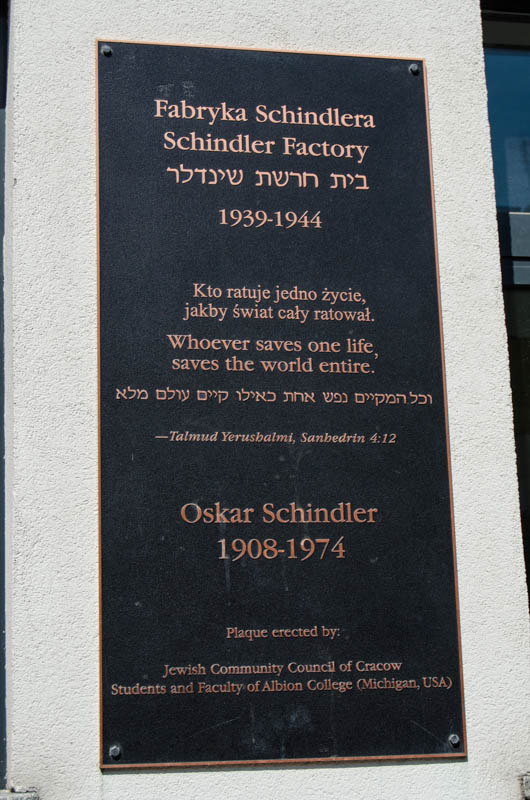

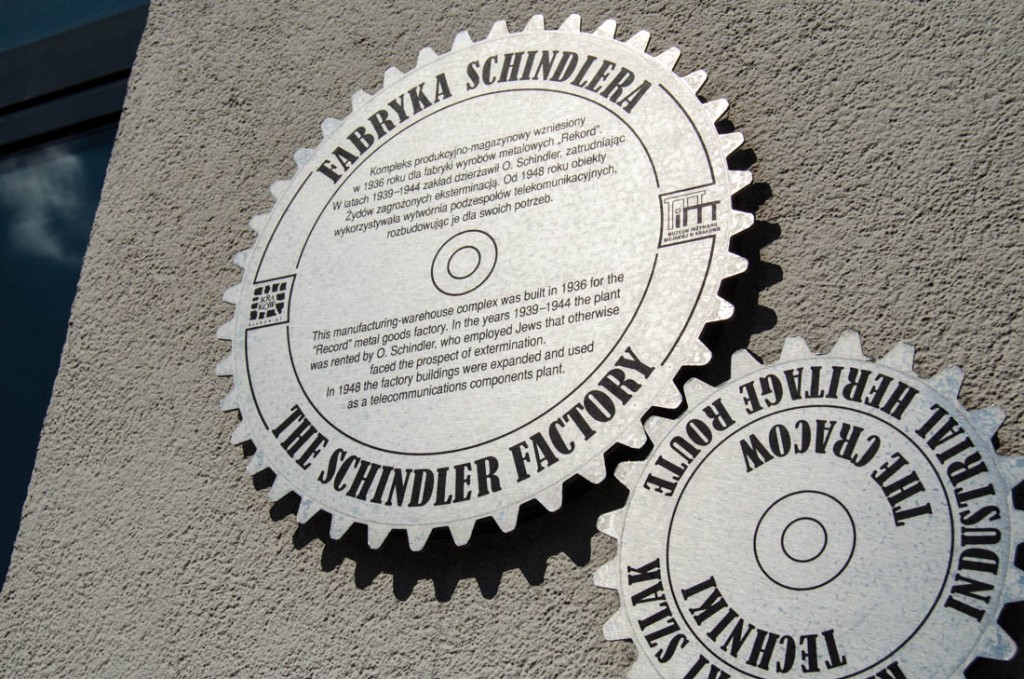

Our Air BnB was actually near the historic Jewish Quarter of Kazimierz, and Chris and I went on a guided tour that started in this area, followed the path of the expelled Jews from Kazimierz into the Krakow Ghetto, and finally ended at the factory of Oskar Schindler. Everyone remembers the Steven Spielberg version of this man, right? In reality, Schindler was a complex guy. He started off his career as a Nazi spy and then became an industrialist, taking over an enamelware (and soon after ammunitions) factory in Krakow after the Nazi invasion in 1939. The factory employed about 1,000 Jews from the Krakow Ghetto. Over time, there is evidence that Schindler experienced a profound change of heart. Although he started off with the sole focus of profit, toward the end of the war he began shielding his Jewish workers from Nazi persecution and deportation without regard to the cost. In fact, he lost his entire fortune supporting his workers and bribing Nazi officials during the war. He would end up saving over a thousand Jews from near certain death in the gas chambers. He is the only member of the Nazi party to be buried on Mt. Zion in Jerusalem.

After the Nazis came the Soviets, and Poland suffered greatly under communist rule. Even more so than in Warsaw (which is saying a lot, since, boy, do the Varsovians love this guy too), the people of Krakow revere Pope John Paul II, who rose to the position of pope from his post as archbishop of the city in 1978. John Paul II’s elevation was historic. Not only was he the first non-Italian pope in 455 years, but he came from a country under communist rule. Thanks in large part to his message of hope and solidarity, Krakow emerged from under the Iron Curtain in 1989 with Polish independence, and its beautiful old town has been attracting loads of western tourists ever since.

Krakow’s Streets and Eats

After learning so much about all the tragedies that occurred on Polish soil, Chris and I had a hard time switching gears after our tours of the Jewish areas of Warsaw and Krakow to going out to bars and restaurants afterwards. We laid low on the very emotional days (especially the day we visited Auschwitz, which I’ll talk about in my next post). On the days we did go out, however, we witnessed a vibrant city. Nowadays, without a meaningful Jewish population any longer, the Jewish Quarter of Kazimierz has transformed from a rough neighborhood during Communist times into a trendy, hipster area with the best nightlife. Chockfull of artists and students, today’s Kazimierz reminded us of Brooklyn or Chicago’s Bucktown.

The main square of the area, called Plac Nowy, is surrounded by quirky bars crammed with outdoor tables during the summertime. In the middle of the square stands a rotunda dating back to 1900 that was previously used as a Jewish slaughterhouse. Plac Nowy is completely different from the old town’s splendid main square. It’s filled with run down buildings and skater kids rather than old cathedrals and elegant hotels. But it has an absolutely infectious energy. One night, Chris and I had a drink at the Singer Cafe, named for the old school Singer sewing machine tables upon which you rest your drinks. Although we didn’t stay out late enough to see it firsthand, our tour guide who lives in Kazimierz told us the place is famous as a late-night bar where dancing on tables is common. Afterwards, we walked through the square and listened to a pianist and cellist play on the roof of the rotunda.

After a couple beers, it’s a Kazimierz custom to visit the rotunda in the center of the square and buy a zapiekanka, the Polish equivalent of a drunken late-night Taco Bell run. A holdover from the austere Soviet cuisine, Zapiekanki are toasted open-faced sandwiches made of half a baguette topped with mushrooms, cheese, and a load of optional ingredients. We got ours with sausage and onion. Yum.

We also ventured outside of Kazimierz to seek out some of the other things Poland is famous for: pierogi and vodka. Both of these have some interesting Russian linkages; the most classic Polish pierogi is actually called pierogi ruskie (with cheese and potatoes), and Poland claims to have invented vodka and exported it to Russia (Russia also claims to have invented the stuff… either way it’s been to Russia’s general demise; 25% of Russian men die before the age of 55, and vodka is largely to blame).

Vodka was originally used for medicinal purposes, and many homemade recipes over the years added flavorings to improve its taste. At the recommendation of the New York Times 36 Hours for Krakow, we visited the vodka bar Wodka (the Polish word for the stuff) and bartender Maciek picked a flight of flavored vodkas for us. Some of the traditional flavors we tried were hazelnut, plum, cherry, and quince. More adventurous was mojito and lemon chili. He also mixed me up a local favorite cocktail called Tatanka: bison grass vodka, apple juice, and a dash of cinnamon. It tasted like apple pie and is my new favorite drink. Chris captured the play by play of me trying a particularly strong one.

I’ll close with the legend of Krakow’s founding. According to folklore, Krakow was founded by a Polish prince Krakus who built his castle on a hill above a cave inhabited by a dragon (Smok Wawelski in Polish, or the Dragon of Wawel Hill). The dragon has been a symbol of Krakow ever since, and you can even pay it a visit and watch flames waft from its mouth ever few minutes. Or, of course, pick up a souvenir from one of the many carts peddling the plush toys.

We had a fantastic time in Poland during our one week here. From beautiful castles and squares to great beer and cocktails (Polish food isn’t widely-reputed, so I’ll leave it off the conclusion highlights :-), Poland has a lot to offer. It was also one of the most emotionally challenging places we’ve ever visited. Seeing the destruction of Warsaw and the remnants of the Krakow Ghetto was heartbreaking. But our visit to Auschwitz would prove to be the most poignant testament we’ve seen to the darkest corners of human nature yet.

Leave a Reply